about the halfway exhibition

The leitmotif of Gábor Miklós Szőke’s first retrospective exhibition is his dog, Dante, who has been his artistic companion throughout his career. 2018 is the year of the dog. In Chinese culture, this year is about consolidation, the mental and physical toils of previous years will bear fruit at this time. The 33-year-old artist has reached an important milestone in his life, after his artistic awakening, his classical training, his debut and ensuing success, how could he deepen his art, while he stays true to his visual language and explores new paths at the same time. This is the question this exhibition seeks to answer. It begins on the lower floor of Ybl House. From here, we get to walk through Szőke’s different periods in chronological order. First we can see his studies from his childhood and university years, then we get to the young sculptor’s lath period, which was born at an art colony, when instead of wood carving, he started building something from discarded boards found on site. During the years, Szőke has further developed this experimental technique and this was the inspiration for the later public sculptures made of stainless steel, which have become the exemplars of Gábor Miklós Szőke’s signature style. The last stop on the lower floor presents the birth of his private mythology inspired by Dante. The arrangement of the works in the exhibition space bears symbolic meaning: as we make way towards the more spacious and lofty halls, so do the exhibits become more monumental and fearful. On the upper floor, we are initiated into the world of public sculptures, which watch over sport stadiums and busy squares in different parts of the world. The ambiance of the artist’s unique studio is re-created in one of the halls, where we can glimpse into the everyday life of his creative workshop through his personal objects, sketches and drawings. The peak of the exhibition is the brand new installation, Halfway, in which Szőke returns to his muse, the cradle of his art, Dante. The year of the dog confronts the artist with several questions: how can he be present, but retreat from the world at the same time, how can he amass new creative energy, while he is conquering new worlds, just as Dante arching empty imaginary spaces, looking into the future and breaking down walls.

the opening speech of art historian Katalin Keserü

The title of the exhibition (Halfway) carries a kind of gravity, since it is difficult to look at Gabor Szoke’s past 7, 8, or 9 years as an independent artist as half of a professional career, but it seems he thinks of his life as part of his work – as he says: for him, existence equals creation -, this is why he puts his childhood drawings from when he was 6, 7, and 8 years old on display as well (all of which were carefully dated by his mother). However, it is not easy being “half way through the journey of our life”. As Dante says, there is “a gloomy wood” half way:

“And ah, how hard it is to say just what this wild and rough and stubborn woodland was, the very thought of which renews my fear! So bitter ‘t is, that death is little worse; but of the good to treat which there I found, I’ll speak of what I else discovered there.” (translation by Courtney Langdon)

The title of Dante Alighieri’s personal story, which begins in 1300 is The Divine Comedy. Could a merry comedy, as opposed to a mournful tragedy, be our guide at this exhibition today?

“Then lo, not far from where the ascent began, a Leopard which, exceeding light and swift, was covered over with a spotted hide, (…) I therefore had as cause for hoping well of that wild beast with gaily mottled skin, the hour of daytime and the year’s sweet season; but not so, that I should not fear the sight, which next appeared before me, of a Lion, – against me this one seemed to be advancing with head erect and with such raging hunger, that even the air seemed terrified thereby – “

I will not enumerate who else Dante met, since they can be seen here around us, together with other animals, which any worthy depiction of Paradise would find important to immortalize, just like one of Gabor Szoke’s childhood drawings from 1992, or Lucas Cranach the Elder’s Adam and Eve, subtly indicating the primeval hopes of man. I mention Lucas Cranach the Elder, because Adam and Eve appear here today, blown up for a young man to appropriate half a millennium later. They were fitted with claws, lush hair and Doberman heads, signaling – less subtly – that despite all attempts to separate them, the monstrous and the beautiful, the animalistic and the humane are inextricably intertwined in the same body and space (Creation, 2010). Similar reinterpretations are very common in contemporary art. Is this a mockery of our predecessors? Or a correction of our worldview, according to which humans and animals are not as different as we thought, as science itself claims? Or is the different, yet similar “Other” simply a product of our childlike/mythical imagination? In any case, the Doberman embodies this kind of duality: loyal, yet fearsome, wild, yet beautiful. This is Dante – who had been Gabor Szoke’s dog for 9 years, and, since his passing, has lived on in the artist’s sculptures and imagination.

Could Dante, the poet, who had been to Hell and Purgatory, who had built up Heaven inside of himself, and who had made this triplicate world accessible to everyone, could he have been incarnated in the dog and its sculptures 700 years later? Could he be stopping the visitors of the exhibition in the form of mythical/fairy tale-like gatekeepers? Dante, the poet’s state of being on the road has become cultic, popular so to say. However, the quote above underscores yet another notion, in addition to the road: “the good to treat which I found there”. Was Dante’s infernal acquaintance with the peculiar and artistic thoughts of Virgil, the late Roman poet already part of that good which he found there? Which could be the creative process itself? And to what kind of paradise does this lead us nowadays?

I know that when he was about 10 years old, Gabor together with his peers had the opportunity to create the kind of art in the famous GyIK Workshop in Budapest, which his loving parents could not have imagined in their wildest dreams. At the Hungarian University of Fine Arts, he developed a perfect sense of anatomy and form under the mentorship of Pal Ko (as can be seen from the bronze horse statuettes). At a university wood carving camp, about 10 years ago – breaking away from traditional modeling – he first assembled an animal-like creature and later a bull from discarded wood. In these creatures, childhood fairy tales, myths, knowledge, reality and imagination gradually came together to form Szoke’s art. But what kind of art is this?

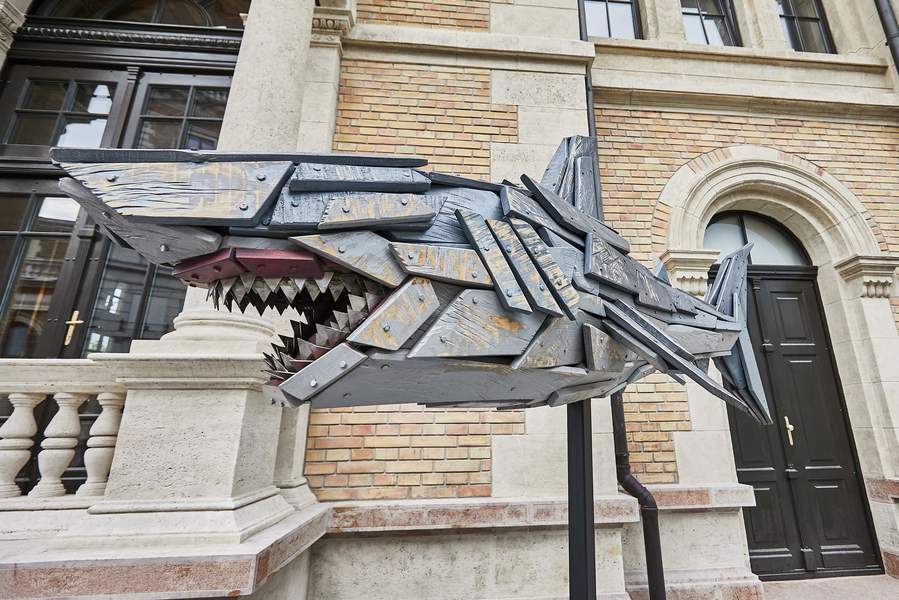

To answer this question, I will review a coherent group of Gabor Szoke’s works, which meet international standards, as we can see. I am the most sorry that today Gabor Szoke’s sculptures, which were once located next to the former building of the Design Terminal in the center of Budapest, are not there anymore. If we survey the photos and models of Szoke’s lath works from the past 9-10 years, we can see that every piece is unique and mature in thought. The colorful horses put together from only a few laths (for example The horse that ate embers, 2009) were different from the huge, densely packed Whale from 2009, the Rocking Horse accommodating 70 people under its legs in Vienna (2010), the colorful birds designed for a playground (2013-14), or the alarmingly windy Chinese Dragon (2015). The predators tamed by their lath life are also different, such as the Guardian Tiger (2012) gifted to the poorest village in Hungary. These bodies riveted together from laths grasp and express movement and character. Their inner skeleton does not simply receive a “cover”, but the working of the muscles is what appears in front of the spectator. Their construction is an attentive and joyful game, and this is why these extraordinary sculptures are so popular, because they speak not only of physical, but also of spiritual anatomy. Something similar could have been said some 50 years ago of certain pop art works. Is this kind of joy childlike? Yes, these sculptures are toys, they express the joy of wildlife.

From the above, the two Pulis (the Flying black one, 2013; and the skateboarding purple one, 2017) and the Guardians of Dante (2011) are emblematic pieces. The first one was monumental, and it visualized the passionate and hard-headed, yet devoted nature of the puli; the other is life-size, always ready to play. The latter is not exhibited here, but they do blur the boundary between animal and man, just as the larger-than-human black Dobermans. Is it our waning humane characteristics which are expressed through these sculptures? They are symbols of human ability, just as the monumental, permanent, stainless steel public works: the race horse tilted in its gallop (Colossus, 2015), the FTC Eagle (2015) and the Atlanta Falcon (2017). It can be seen from the proportions, the material (steel), and the technique (welding) that they are similar to design objects and are made through team work, but cannot be replicated like a Peugeot logo: a wild, roaring lion with its mane blown back embodying the civilizational victory of design and speed. They cannot be copied: not only because the design is personal, while the animals, which symbolize extraordinary achievements and inspire similar feats, summon mythical powers; but also because their construction is a performative and communal process in the widest possible sense, including the animation of the animals. A peculiar example of all this is the emergence of the stainless steel bear from the fire in Moscow (Maslenitsa, 2016). This wasn’t the artist performing as usual, but the animal. How deep is this compassion, which is able to do this not only with the animal, but with the nation, which sees itself in the bear! Thus, the never-forgotten characters of our childhood and the childhoods of other people come to life.

Are we re-living the childhood of humanity? Perhaps, but if so, it comes with the unheard-of abundance of the emotions of love, horror, joy, compassion, fear and awe, which are in short supply nowadays. Could this be the “Good” (with a capital letter)? The essence of human culture long missing since the golden age of so-called individualism? In which all creative acts are dedicated to the “Other” (the others)?

What could someone, who has already lived through the other half of their lives, say to this? Thank you, Gábor, for bringing us into an almost unknown world. We thank you as a parent thanks a child, who does everything differently from its predecessors. And thanks is due to the organizers of the exhibition, Berta Hauer and Kata Kaiser. This way we might not forget what we are, what we were, and what we could be.

Selection

works

The beginnings

Hungarian folktales and the animal world captured Szőke’s imagination at a very young age. One of his earliest memories is from a relative’s farm at the age of 5-6, when he found himself face to face with some horses locked in a stable. From his perspective then, the animals seemed scary and superhuman. According to the artist, this experience paved the way for the themes and monumental scale of his later public works.

lath sculptures

At a university wood carving camp, Szőke was not in the mood to carve, thus he found a pile of laths left from a demolition, and the discarded building materials immediately got his imagination going. He wired together thin laths and trimmings and named his first creature Tikito, a word from his baby language, he used for every new discovery he made around him. When he returned home, he started experimenting with boards and planks of different sizes and his first two lath sculptures were born, a bull and a wild boar. He deconstructed the most common motif in his works, the animal depicted in tension, into elementary units, blocks, or more precisely wooden boards, and then with these, he re-constructed them again. During this creative process, the artist discovered his first individual means of expression, the board, the paradigmatic effects of which can be felt in his visual language to this day.

the horse that ate embers

The horse that ate embers is the miniature version of the central figure from the installation Horses in the Castle Park. The work featuring 9 horse sculptures was first exhibited in the park of the Helikon Castle Museum in Keszthely, then it was shown at the Nagytétény Castle Museum and Millenáris Park. With the open-air arrangement of this piece and the distribution of weight and colour, Szőke was experimenting with guiding the viewers’ attention from one element to another with the individual dynamics of the nine horse sculptures.

dante sculptures

ivanka conrete mixer

For the 2010 Milan Design Week, Ivanka Concrete Design commissioned Gábor Miklós Szőke to create the Concrete Mixer to be presented at Salone Satellite. The composition was inspired by the plaster cast of the dog from Pompeii. The two dogs are an allusion to the unbreakable bond between Katalin Ivánka and András Ivánka, the founders of the globally successful Hungarian concrete manufacturing company.

Bathing dante

In this ironic Dante sculpture, the canopic jar is actually a plastic barrel from the house of the artist’s grandfather, which was used for pressing grapes during harvest. The Bacchanalian drama of Dante stuck in thick tar is also a promise of artistic re-birth.

the cradle/coffin of dante

This piece was made in 2010 in the size of the artist and it has been part of many exhibitions and performances. Inspired by Egyptian sarcophagi and made from wooden planks, the unearthly feel of the coffin alludes to Dante’s cradle and the duality of its nature, by which he was born from his own demise.

the rococo feeling of the dante empire

Dante appears at many points throughout time and space from primeval times to the distant future. The lavishly furnished interior was inspired by Fragonard’s paintings and the rococo. On the sofa, Dante’s love, Trixi is resting. Trixi was a real dog, the artist’s other doberman, whom he bought without knowing her name beforehand. A few days after the dog arrived, he realized that Trixi is short for Beatrice. On the wall, the double portrait bursting with golden foam titled Dante in Love was born from the adaptation of a found painting. It depicts the artist and his love, Berta. After establishing his empire, Dante reformed the taste of his court, which affected the style of the furniture as well. Part of the composition is a prototype of the 2011 Dante table and chair collection, which was chosen as one of the top ten pieces of design furniture of the year in Hungary. He named this style industrial-imperial.

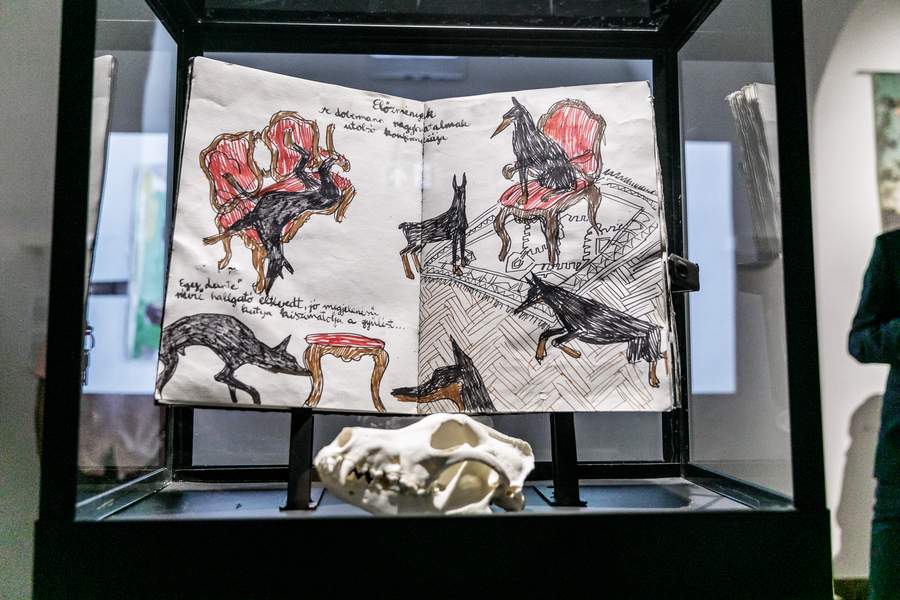

the book of dante

It started as a university sketch book. Full of irony and horror, creation and destruction, this book has been a source of inspiration for the artist for 10 years. Through Dante, the pages of the sketch book tell us about finding oneself, self-irony, utopias, monsters, self-entertainment and shocking people. There are several chapters, which seemed like fictitious wanderings of his imagination. Only later did he realize that some episodes have been coming true, such as the Dante furniture line, the giant Rocking Horse, the Dinosaur installation and Dante’s conquests around the world. Beside the book, the skull of Dante, the artist’s dog can be seen, like an allegory of the book’s spirit, a relic of Szőke’s unforgettable muse.

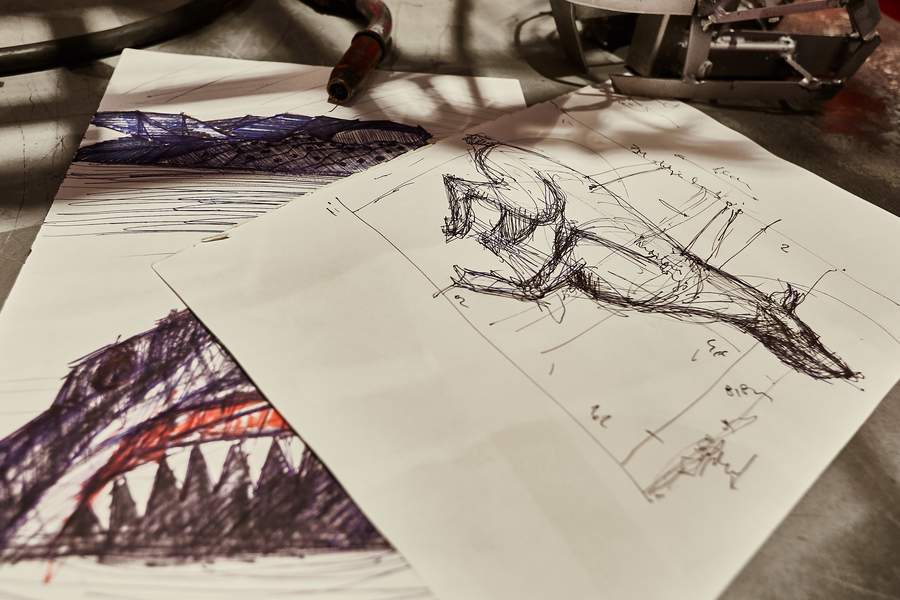

the studio of gábor miklós szőke

Gábor Miklós Szőke’s first studio was the family garage, today it is a 100-year-old, 4000-square-metre industrial complex located in the former Manfréd Weiss Steel and Metal Works. The estate, which includes the office, the showroom, the workshop and warehouses, is co-owned by the artist and his partner and it is the headquarters of the Dante Empire. Crossing continents and oceans, this is where the artist’s sculptures start their journey, this is where his clients and guests come. The studio also hosts various thematic social events and it has facilities befitting an industrial construction company. Every detail of the studio reflects its owners’ taste. The kitchen, the locker room, the offices, the furniture, the banister and the stairs were all made by the team of Gábor Miklós Szőke. During the renovation of the halls, it was an important aesthetic principle to restore the WM Works to its former glory and to reinterpret this industrial historic building in Szőke’s style. From the facade to the interiors to the uniforms of the workers, the dominant colours are black, red and white. In 2017, the Gábor M. Szőke Studio won Hungarian Design Office of the Year.

halfway

In the year of the dog, the artist returned to his muse, Dante. The sculpture titled Halfway filled the largest hall of the Ybl House. The deliberately exaggerated scale of the dog has a dream-like effect between the neo-renaissance walls. It levitates in the air, which only adds to its mysterious character. With this enormous Dante running in a closed space, the artist brings his monumental sculptures closer to the visitor. The sculpture was inspired by a water-colour painting depicting a Chinese foo dog flying above the mountains. Dante dominates the space, but he is only halfway, he wants to develop and form his surroundings.

opening and closing event of the exhibition

contributors

Artistic director: Katalin Kaiser and the team of Ybl Budai Kreatív Ház

Curators: Berta Hauer – Gábor M Szőke

Text:

Viktor Grásztity

Berta Hauer

Gábor Miklós Szőke

Revised by:

Katalin Kaiser

Lajos Hauer

Graphic design:

Anna Nagy

Dániel Bálint

Exhibition cover photo by: Márk Viszlay

Photographers (in order of photo’s appearance):

András Vikmann

Barnabás Tóth

Éva Szombat

Márk Viszlay

Enikő Hodosy

Tímea Szőke

Films:

Halfway documentary: OMG Visuals

Maslenitsa, spring awakening: Márk Viszlay, Péter Juhász

FINA World Aquatics Championships: 235 Production

FTC Eagle: Márk Viszlay, Gábor Miló

Showreel: Péter Juhász

Falcon films: Péter Juhász

The artist’s permanent team:

Balázs Magyari – head sculptor

Csaba Németh – sculptor

Zsolt Bajári – sculptor

Zsolt Molnár – AVI welder

Csaba Kakucsi – AVI welder

Ferenc Éliás – production manager

Babszi Kiss – office & marketing

Krisztián Kovács – woodwork engineer

Márk Filus – 3d modelling

Áron Dawson – structural engineer & technical drawing

Berta Hauer – communications & project coordination

Partners:

Panelko Kft

Inoxil Kft

Ivanka Concrete

Szilard Baraz / Kálmán Furák

Giacotti

Belight

Remmers

Logistics: KUK-team

Production of wall texts:

KNK PR & Media